I know, I probably offended some people by saying that I don’t particularly agree with configuration management scripts being used for infrastructure provisioning, middleware installations, and code deployment. That’s because I see certain places where this could potentially fit, but in others adds complexity.

To begin, I wanted to run over a couple of scenarios of using static infrastructure, and configuration management tools the wrong way.

Let’s Run over a Couple of Scenarios

If we’re to run this design over a couple of scenarios we can easily see where this might all go wrong.

Scenario #1:

It’s 2am. Your on-call person has just been paged with a severity one issue in production. An AWS availability zone has gone down due to a catastrophic power outage in their data centre. Your on-call person realises that they are now running on one server, and that server is beginning to get hit by a large number of customers who probably want to book last minute tickets to that concert everyone has been talking about. “Shit, shit, shit. Where was that Ansible script to provision a new server and deploy the application?” they ask themselves.

The on-call person manages to find the Jenkins job that deploys to these servers, and finds the source code which has been deployed directly from the Jenkins box and not stored on an artefact repository. It’ll have to do! He then manually logs into the server and runs the app. “What were the JVM options? Fuck it, we’re going with default!” he says and runs the app. The default spring profile is now pointing to a test database, and customer data will now be freely available to the QAs. Excellent. Now that the app is up and running, he needs to add it into the load balancer. “Shit, which load balancer did this sit in?” The on-call guy now puts the new server in the load balancer and watches traffic even out.

While he thinks he might have succeeded, 40 minutes have now passed, AWS restored their availability zone 15 minutes prior to that, and the server that was running on its own shut down.

To add further insult, a server has been manually provisioned (running a script yourself doesn’t make it automated). This server was provisioned on a script which was 20 commits older than the server that had been originally provisioned. What’s the difference? Well, the new server is unsurprisingly running on an older AMI, no monitoring has been set up, and the hosts file wasn’t updated in all of this mess. Tomorrow, the development team will find themselves no being able to deploy to their second server in AZB because it no longer exists. I’d call this a complete an utter failure which has introduced instability, and has operationally regressed. If this server is to go down for whatever reason, nobody is going to know because there is no monitoring.

Scenario #2:

Your team has just found out that the prod deployment SSH key has been sent to a partnering team via email (this happens more often than you’d think). It’s now safe to assume that this key is compromised, but you have no idea which servers it has been used on. You also have no idea which other keys might have been sent in an email. After raising this with management, they tell you that all of the keys in production will need to be replaced. This doesn’t seem too hard until you realise that you’re running 800 servers, and will also need the development teams to update the SSH keys that their deployment boxes use. This becomes a big, stupid, non-value adding task which takes teams weeks to complete while also not resolving the core problem.

Scenario #3:

The smelly monkey vulnerability has just been announced, and all of your servers in production will need to be updated to the newest AWS AMI or manually patched. With the amount of servers running on AWS, patching this zero-day vulnerability will take weeks of planning and orchestration. This is mostly due to the fact that the organisation is operating with static infrastructure. There is another team altogether which will need to patch every server individually while having another representative from each application verify that the change has been successful and hasn’t broken their production server.

Working with these kinds of scenarios helped us determine what it was that we wanted to combat and change.

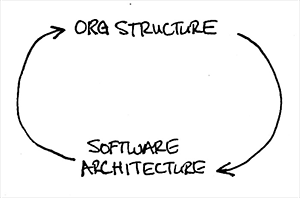

Working within the Constraints of the Organisation — Understanding Conway’s Law

Before we began working on a solution, we needed to first do some analysis which would impact the technical implementation of our infrastructure. Infrastructure in larger organisations is heavily tied to the organisational structure (See: Conway’s Law).

While I’m not saying that you should just accept that things are the way that they are, you aren’t in any position to go against it. Especially if your organisation is not yet sold on DevOps. Most organisations will take on a command-and-control mindset, instead of an audit-and-monitor culture. A lot of this could also be due to the nature of the organisation you are in. Financial Institutions will be a lot more risk averse compared to those who aren’t as heavily regulated.

As a result of this, you realise that you need to work within constraints at certain times, as you probably can’t have all of the things that you’d like. For instance, we ran into a few things that we had no power to change. This also affected the architecture of our app, but we didn’t let this stop us from building the system to be as resilient as it could be within its constraints. Some of our constraints were:

- AMI Creation was owned by another team. Since we didn’t have the power to create AMIs with our middleware installation on them, we needed to think of another way to replicate the same kind of functionality. We worked around this by using EBS Snapshots.

- Networking was owned by another team. This meant that using something like Route53 was out of the question since the organisation used another solution to expose services to the public. This affected our blue/green deployment strategy, but we decided to use static ELBs and do the blue/green deployment via an attach/detach of our AutoScaling Groups to our ELBs.

Understanding the constraints of the organisation you are in really helps, especially in larger organisation. Consultants will usually come into an organisation promoting an architecture, deployment pattern, or a technology stack that isn’t feasible either due to the organisational structure, or the technical limitations that the organisation imposes. Spending time understanding the constraints of the organisation can be a tedious and time consuming effort, but ultimately pays off when designing a system.

Change Management

Change management plays a very big part in any organisation. Now matter how good your implementation may be, and no matter how risk averse your new set of automation provides you, you’re not going to make very significant progress unless you get the Change Management Team involved in what you’re doing. The philosophy of DevOps emphasises the need to minimise the batch sizes in your changes in order to minimise the risk that a particular change introduces (Continuous Delivery). However, what you’ll see in larger organisations is that changes are orchestrated by a larger committee or board which tries to ensure that a particular change will not affect other applications.

That being said, while this board is able to see what the changes are that are being made, it still does not mean that a particular change will be successful. The mistake that most larger organisations make is that the approval that a Change Board gives ensures that a change will not break. So, when things do break, the assumption is that there aren’t enough risk controls in the change management process. And so, the extra controls are put in place, which increases the complexity of a change. While this may seem like it may fix some problems associated with change, it also enforces a particular behaviour in teams which are actually making these changes. The harder the change is to make, the less likely it would be for teams to make changes on a regular basis. As a result of this, the batch size of a change increases from small, easy to roll back, and easy to test changes into large, clunky, hard to roll back changes which take hours to test.

While this may not be the most fun part of any piece of work, you’ll need to spend some time with the Change Management team in order to understand why certain steps exist in the change management process in order for you to influence the process.

**Understand the Change Management Process — **What are the risk controls that they’ve added into their process? Are you able to automate this in order to minimise the likelihood of a particular risk?

**Understand what risks are being introduced with each manual step in the process — **Once you understand the risk controls, you’ll also be able to understand why they are there. A lot of the time, it’s to do with the risk associated with manual steps that teams make. This could be anything from schema changes in a database, to new servers being created in the cloud.

**Automate as much as you can — **Now that you know what the risks are with certain steps in the process, you also know what you need to automate. This isn’t just about automating a certain thing to happen. You also need to automate the testing once that change has been applied, and the rollback if the change isn’t successful.

**Define and Measure Failed Changes — **In most traditional organisations, IT teams making a change will potentially spend hours making that change. A lot of it is to do with the fact that during the testing of that change, something might have gone wrong, devs might have had to deploy a hotfix, or schema updates to a database were not successful. The team eventually does make the change after applying all of these extra changes on top of their initial change, and calls it a successful production release. I’d call this a failed change.

**Make Failed Changes Visible — **In order to build trust, you need to have transparency over your work and what it is that your team is doing. Using metrics to measure the amount of failed changes you make is indicative of processes that you need to improve. Knowing why a change failed identifies what needs to be automated or improved.

Keeping the Change Board involved in these steps you’re taking in minimising risk end-to-end helps to build confidence in the team and the changes that the team is making. Being transparent with your failures helps the Change Board gain trust in your team. If your organisation has the concept of pre-approved changes in the change process, find out what it is that you need to do to get to this point.

What did we Build?

We set out to not only build infrastructure, but also try to solve as many of the operational problems as we could within the constraints and deadlines that we had on the project.

We decided to use CloudFormation as a deployment tool. I’d love to hear your opinion on this, but we found this to be a lot more powerful than Ansible.

One of the powerful things we found with CloudFormation was that we could script our deployments using AWS API commands. As part of our deployments we would:

- Create a new AWS stack running the newest version of the app.

- A smoke test would run on the app ensuring that it can hit all of it’s dependent service endpoints.

- It would get attached to the ELB running the current production version of the app. This means that we are running 2 versions of our app at the same time (see BlueGreenDeployment).

- The old AutoScaling Group would be detached. The deletion of this stack would be a manual step in-case we need to roll back.

We used an AutoScaling Group to create our EC2s because we wanted to ensure that we weren’t pushing out any configuration, but were depending on our infrastructure to configure itself. We used CloudFormation to ensure that we were just defining what we wanted it to look like, and let AWS do the rest.

The way we were able to do a lot of this was by using a bootstrapping script in our snapshot which would run as soon as the server was instantiated. It would run whatever scripts it needed to lock down our servers, and then pulled down the artefact from an external artefact repository. It would then run it, and do a basic uptime check. Once the app returned a HTTP/200 we would signal back to CloudFormation that the server creation was successful and we had something running. By doing this, we could ensure that our code deployments weren’t blowing up our servers and especially helped us quickly realise if we were deploying a breaking change. The fact that this was a separate piece of infrastructure meant that our production deployments were incredibly safe and wouldn’t incur any kind of outage.

The only Ansible we ended up using was to create our EBS snapshots. We found Ansible to be incredibly useful and powerful for this, as we could easily template a lot of our configuration files and write the middleware installation in an easy-to-read syntax (unlike CloudFormation templates which are curly-braces galore).

While this solution isn’t exactly ideal, as many of you would likely have more to your disposal when architecting your applications in the cloud. But it gives us a lot that we didn’t previously have before, which is a great start to getting more available.

So, What does this Give us?

The most important thing we get out of this is completely dynamic and ephemeral infrastructure. Every deployment of our code triggers a build of new EC2s. The fact that this is done via CloudFormation as well means that even the stack name can be programatically set (in our case, we prepended our name with a timestamp).

CloudFormation stacks give us more visibility of what we’re running. Simply by looking at our CloudFormation parameters, we can find out what AMI version we’re running on, we can determine what Java version we’re using based on the tags of the attached snapshot, where this has been deployed, and what artefact version we’re currently running.

EC2s pulling their artefacts in, means that autoscaling is now actually possible. This together with cfn-init means that the app is constantly being tested and developers gain a lot more confidence in the resiliency of their infrastructure. This also gave us the added bonus of more resilient infrastructure, as the AutoScaling Group would deal with creating a new EC2 if the total number of EC2s was to fall below the desired amount.

Infrastructure patching like AMI updates became extremely trivial, as all we needed to do was update our parameters in our CloudFormation script and watch it be deployed through our environments.

Essentially eliminating the need for SSH access. While it is still good to have break-glass SSH access into our servers, SSH key management is practically a thing of the past. This removes one vulnerability from our infrastructure.

Deployment being an API call means that the development team is in control of how they deploy in a language that they are most familiar with. This direct and convenient control over deployment script means that the developers are much more likely to update the automation on their deployments over time.

Monitoring criteria changes. Because our AutoScaling Group is now monitoring our CPU usage and using it to either scale out or scale in our infrastructure, we no longer need to monitor this per EC2. Our ELBs also do health checks on particular pages, and use this to determine whether or not load is to be balanced to those EC2s. This means that one of our critical alerts now becomes “EC2 count in ELB”.

What Cultural Changes did we see in the team?

When talking with the developers and telling them that we were going to work towards fully automated deployments from QA all the way to Prod, it seemed to pique a bit of interest.

What we ended up with was hours of discussions about deployment patterns, practices, preferred technologies to use, and lots of whiteboarding. It was honestly refreshing to watch the Devs really caring about making these deployments as safe and secure as possible, as opposed to the usual culture of throwing code over the fence and hoping that it works.

What the Devs also got out of this was a greater understanding of the AWS Services available to them. We then started discussing ways of making our CI builds more visible by pushing build statuses out to Slack, and even looking into using Lambda functions to propagate critical monitoring alerts to a dedicated Slack Channel as well.

We also saw discussions begin in the team about feedback loops of our deployments, and basically rethinking our testing and deployment strategies. Smoke tests that ran during deployments would be stripped down to check for basics, while more robust smoke tests and code scanning tasks would run as a nightly job.

In our case, what we noticed was that the easier and more automated operational issues such as monitoring, deployment strategies, production outages and rollbacks became, the more willing the team was to enhance them. Being able to constantly tweak your monitoring to ensure that no one would be getting false positives greatly increases the criticality that someone perceives when a monitoring alert is actually triggered.

How will this battle win over The Organisation?

If you work in an enterprise environment, you would have noticed that consultants will come in and give you a suggestion on what you could potentially be doing. Sometimes they even have a little demo to show off. Being able to actually achieve it within the organisation while also taking its constraints into consideration, you can win over a lot more people.

You need to be able to first win over your own team. Get them to see the value in what you’re looking to change, and keep them involved in this work. Get their feedback on what their pain points are really helps to drive work in your DevOps Transformation.

Keeping other teams that enforce constraints as well as involving management in what it is that your team is doing really helps. Try and frequently showcase what it is that you’re working on to other teams, and get them interested in what you’re working on.

Have something great to show them. Maybe get approval to kill off a production server as part of your presentation and show off the resiliency of a system they already have running in production. The most powerful thing you can do is show them that this is possible, and that it’s already being done.

In Conclusion

Quite honestly, it doesn’t matter what kind of technological approach you take. We went with CloudFormation as it was our path of least resistance. It gave us the flexibility to approach deployments with our own set of tools, and it gave us the visibility we were missing with conventional configuration management tools.

Once your infrastructure is dynamic, it gets much easier to iterate on it and improve it over time. Again, this won’t make you DevOps. Always keep in mind the processes behind all of these technologies you’re introducing and whether or not they allow you to deliver value quicker and combat tedious operational tasks.

Once your organisation is sold on the value that DevOps culture and practices bring, focus on SRE. Build better, build quicker, and build resilient systems. There’s absolutely nothing stopping even the biggest and oldest of enterprise organisations from Being Netflix.

So, if you’re finding yourself in a similar position, you might want to do a couple of things before trying to sell the organisation on DevOps.

- Map your dependencies. If your infrastructure hits multiple internal endpoints, it’s best to find this out ahead of time.

- Form relationships with people who are in these teams. Taking them on this journey with you will help them understand the kind of work they need to drive in their teams.

- Understand your constraints. You might not have certain things available to you such as Docker, or AMI creation, or full access to AWS services which lets you use Netflix OSS. Sometimes doing some of the hard work is necessary if you need to win people over in additional improvements you can make.

- Take your team on this journey with you. In order to get buy-in from other teams, you’ll need buy-in from the rest of the team first. Ultimately, you want to be benefitting your team by giving them less to do.

- Talk to other teams, and find out what their pain points are. Take this into consideration when architecting a solution. You want it to be easy enough for teams other than your own to pick up. Also, if you address some of their pain points directly, you’ve already won over some very important people.

I hope these short ramblings were at least a bit informative for you. I’m not saying that this is essentially a surefire way to introduce DevOps to your organisation, but I think that I have at least given you a good place to start. Enterprise Organisations are a bit of a beast, and I hope you enjoy the challenge of trying to change it as much as I did.

If you can introduce this kind of change to one of the hardest environments to introduce change, it’ll be even easier to do it anywhere else your career as an awesome-devops-transformation-evangelist may lead you!